Special thanks to Thomas for his great feedback and review

Introduction

Ethereum today relies on BLS signatures for attestations. These are compact, aggregatable and battle-tested, yet they are built on elliptic-curve assumptions which means that they are not post-quantum secure. Lean Ethereum is an experimental roadmap that is aggressively simplifying the base layer of Ethereum. One of its tracks is focused on moving to a post-quantum secure setup. In that world, XMSS style signatures become one of the main candidates to replace the existing BLS signatures.

In this post I want to walk through the XMSS signature scheme and how it is adapted for LeanSig, the proposed signature scheme for Lean Ethereum. Mostly I'll explain this paper as best as I can. The goal is to go through these ideas:

- How XMSS roughly works

- The notion of incomparable encodings

- Building a generic protocol to verify signature aggregation via a succinct argument system

- A nice optimization trick to make signature verification super efficient.

XMSS Signatures

XMSS is a hash-based signature scheme that is designed to be post-quantum secure. It's based on two things:

- A One Time Signature (OTS) scheme (Winternitz) built from hash chains.

- A Merkle Tree that bundles many one-time public keys into a single one.

We start with one-time keypairs . Recall that for each , the secret key is a vector: and each component defines one hash chain. The corresponding public key consists of the result of repeatedly hashing , meaning that for each component :

The idea is as follows:

- For each pair, define as a leaf in a Merkle Tree. After all leaves are defined, construct the tree.

- The Merkle Root acts as a public root such that one can always show (via a Merkle Proof) that some is a leaf in the tree whose root is

Now we need the Winternitz-OTS scheme, which works as follows:

- To sign a message use a one time secret key to produce a one-time signature that reveals some information to the Verifier so that it can reconstruct the corresponding one time public key

- Finally, attach a Merkle Proof that shows is a leaf in the Merkle Tree with root

The idea is that hashes are one-way functions and therefore one cannot efficiently obtain from . It's important to note that each key should only be used once.

The signature scheme basically consists of two algorithms, signing and verifying. The signing algorithm would work as follows:

- To sign a message , first one encodes the message , with randomness , into a vector

- Afterwards we use as the steps to take in the hash-chain. So signing involves:

- Converting to and

- Hashing each component of (decomposed in values) a number of times.

Here, is the number of hash-chains and is the Winternitz parameter (bit-width). Each chain has length . Together, the one-time signature and the Merkle Proof are the signature over the message

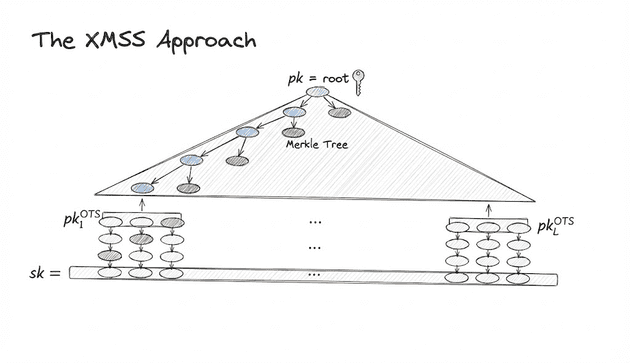

XMSS Approach based on this presentation given in the Ethereum PQ workshop

XMSS Approach based on this presentation given in the Ethereum PQ workshop

Verification of a signature, would involve the following steps:

- Recompute from the message

- For each complete the hash-chain by hashing the remaining steps, until reaching

- Finally, verify that is included in the Merkle Tree with root

Parameters

Before diving into what folks working in Lean Ethereum did, I want to give a picture of what happens when you change the parameters in this scheme. The two most important parameters are (the number of hash-chains) and (the number of steps from to ). They both target different issues:

- The number of hash chains is important to prevent collision resistant encodings of messages. If there are multiple messages that map to the same encoding, then the scheme is not binding, since one could potentially find that the same signature could be used for different messages. Larger expands the encoding space , reducing collisions.

- The number of steps is important to prevent pre-image attacks. If an attacker can effectively reverse a hash-chain, it might find , breaking the security of the scheme

The signature size (in bits) is: while the work that the prover and verifier together must do is hashes. Note that in a blockchain context we want both small signatures and fast verifiers.

Incomparable encodings

The notion of incomparable encodings is important in order to create a scheme where we can't create signatures for messages if we don't know the secret key

Definition (Comparability). Two different codewords and are comparable if one dominates the other coordinate-wise, i.e., for all and for at least one .

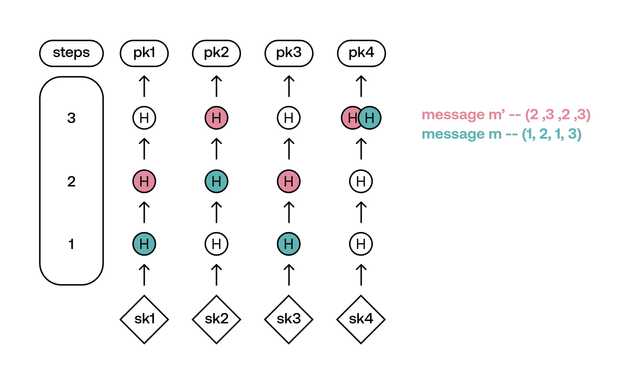

For example is comparable with or but it's incomparable with or The idea is to find an encoding function that gives incomparable codewords from a message . Having incomparable codewords means that the protocol is secure. The reason for this is that whenever we get an encoding from a message we are effectively getting the number of steps to hash on every chain. If there is at least one message such that its encoding is comparable then we could generate a valid signature without knowing the secret key, just by continuing to hash from a known encoding

Encoding of messages and where the encoding of can be constructed solely based on the encoding of and not based in the values of . Here, the encodings of and are comparable

Encoding of messages and where the encoding of can be constructed solely based on the encoding of and not based in the values of . Here, the encodings of and are comparable

Therefore, to prevent this from being able to happen, one needs to generate an incomparable encoding such that producing is simply not possible.

Achieving incomparability

In order to achieve this property and ensure the signature scheme is secure, one needs to propose an encoding that never allows this to happen. Note that we only need one hash-chain to have an element that is less than an existing one as that would be enough to prevent any issue from happening. Recall that reversing a single hash (using a secure hash function) is not feasible. The easiest way to go about this is to add a new value to the code which we would call a checksum. The checksum can be written as .

Let . This is the maximum value any coordinate can take (since ). Note that this would add more elements to (increasing the signature size) but would always provide an incomparable encoding because of the fact that dominates if and only if for all and for at least one .

Hopefully that sounds familiar, it is the definition of comparability we just gave before! Hence, whenever we have an encoding dominating , the checksum of would be less than the other one, making them incomparable, since:

as long as dominates component-wise (so ).

There is a better way to do this which does not increase signature size. It's called Winternitz Target Sum and it consists of simply adding an extra-check to the verification phase:

- Whenever you get , verify that:

Intuitively this works because of the same reason as before. Since is a fixed parameter, then if one were to obtain some dominating component-wise it means that the sum of its components will be greater and therefore will be at least with .

This does add more work for the prover, but it's required to guarantee that the scheme is secure.

LeanSig

Now we are ready to talk about LeanSig, the new construction that is based on these ideas and will be used to replace BLS. Ethereum requires attestations from validators once per epoch. Therefore, each keypair will be used to attest in a single epoch.

The idea is that each validator, when joining the network, generates keys for a number of epochs in advance. The amount of epochs is still not defined, but should be enough to last multiple years, or even decades.

Key Generation

Let be the number of epochs, then the algorithm works as follows:

- Sample a random public salt

- For each epoch :

- Choose random secrets

- Compute the public value by running the chain to the end of its range ()

- Define and

- Place each as leaves of a Merkle Tree and compute the root

The public key is

Signing

In order to sign a message at epoch with secret key :

- Generate the Merkle Proof from to

- Encode the message using an incomparable encoder: where is a fresh random value.

- Note that is randomized and fallible: the signer keeps sampling new values until the resulting vector fulfills the target-sum condition. This makes signing more expensive but results in cheaper verification.

- For each , compute

- Set

The final signature is:

Verification

Given a public key , an epoch , a message and a signature the verifier:

- Recomputes from the message and randomness

- Checks that is a valid element in the code (via Winternitz Target Sum)

- For each , finish computing the hash-chain:

- Set

Finally, the verification only needs to check if is the Merkle Path from to to be done.

From many signatures to a single proof

So far we have only seen how a single validator produces a single LeanSig for a message at epoch . But we are really looking for an aggregated signature to replace BLS such that:

- We have validators, each with a public key

- They all sign a message at the same epoch

- We are looking for a single object convincing us that all signatures are valid.

We won't get into the entire aggregation approach, but rather talk about how to generalize it to a statement that can be later used by any proving system. Let's define a relation that captures that "all signatures are valid". We can define that as:

- The statement:

- The witness:

Recall that would be the signature that each validator generated. Thus, the relation holds if and only if the verification for each validator is succesful:

Note: LeanMultiSig won't involve only aggregating signature verification, but also aggregating aggregation proofs. For simplicity, we will only talk about signature verification here. For the full aggregation protocol, see this post on folding-based post-quantum signature aggregation.

If we take any SNARK where we define and as their proving and verification algorithms, then we can define the LeanMultiSig scheme as follows:

Key Generation and Signing

Both key generation and signing are the same as in LeanSig since nothing else is required.

Aggregation

To aggregate, given , and the list

- Construct and as explained before

Proving

- Compute the aggregated signature as the proof where is the random oracle used by the SNARK implementation.

Verifying

- Given the list of public keys , the epoch , message and the proof run:

- and verify that

Instead of verifying separate hash based signatures, the protocol only needs to verify a single succinct proof. The cost of validation is decoupled from the number of validators and tied instead to the cost of running the proving system itself.

A geometric detour: layers in a hypercube

The follow up paper At the Top of the Hypercube digs into a very specific but important question:

How should we choose the codewords in order to get the best tradeoff between signature size and verification time?

The idea is as follows: Since verifying signatures is what we will have to do in the Verification Algorithm of our proving system, can we make the verification very fast while keeping the signature size small? In other words, could we encode in a way where the signer does most of the work but without requiring us to decrease the hash-chain length (i.e., reducing )?

The answer is yes! By forcing the encoding to lie in the top layers of the hypercube (very close to the chain ends), we force the signer to do the heavy lifting (hashing many times), while the verifier only needs to compute a few remaining hashes.

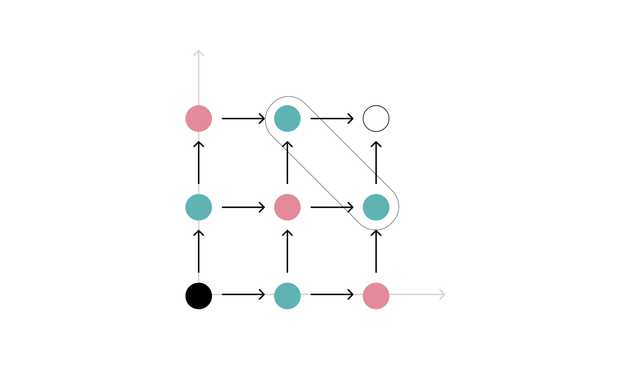

To understand it, we need to get a more proper intuition of the problem. So, consider all the possible codewords as points in a -dimensional grid: where

For reference, a value may be where is repeated times. The idea is that there is a directed edge from a point to a point if:

- For some , and for all

So, for instance if we have and then since but for all we would have a directed edge from to

A 2-dimensional grid of a walk from the source to the sink . Each point is a coordinate and each edge fulfills the aforementioned condition. The top layer is shown and corresponds to the points and

A 2-dimensional grid of a walk from the source to the sink . Each point is a coordinate and each edge fulfills the aforementioned condition. The top layer is shown and corresponds to the points and

Note that if we count the distance from each point to the "sink" we start seeing layers at the same distance, and importantly two properties hold:

- Points in the same layer turn out to form an incomparable set under the coordinate wise order that we care about. Since they are the same distance away, the sum of their components is always a constant , which complies with the Winternitz Target Sum we saw before.

- The value directly controls how many hashes the signer does. Therefore, if we could always get an encoding on one of the top layers, the verifier will have very little work to do.

The paper then proposes different encoding schemes that improve the verification cost when compared against existing schemes, the idea is to use one of those encoding functions as

Note: This encoding is currently state-of-the-art in the spec, but it turned out to be unfriendly for SNARK implementations (because of big-integer arithmetic), and ongoing work is exploring alternatives. It might not be the encoding used in the final design.

Why this matters for Ethereum

Quantum computers threaten elliptic curve based signatures like BLS, but hash-based signatures tend to be bigger in size and compute. Ethereum is a p2p network with big constraints on bandwidth usage; Therefore, new research is required in order to create implementations that can provide good alternatives.

The LeanSig proposed design improve existing constructions by:

- Optimizing the generalized XMSS signatures with incomparable encodings that are cheap to verify and do not worsen the signature size.

- Create a generic statement that can be proven by a specialized argument system in order to aggregate each validator signature.

There is also work done on the aggregation part regarding the concrete proving system to use for LeanMultiSig, though I'll leave that for a future post.